A phase 2 trial just concluded shows that people with celiac disease may now be able to hope for a cure, through a treatment that makes the immune system tolerant towards gluten. This could eventually make it possible for such individuals to eat gluten-containing foods without fear.

What is celiac disease?

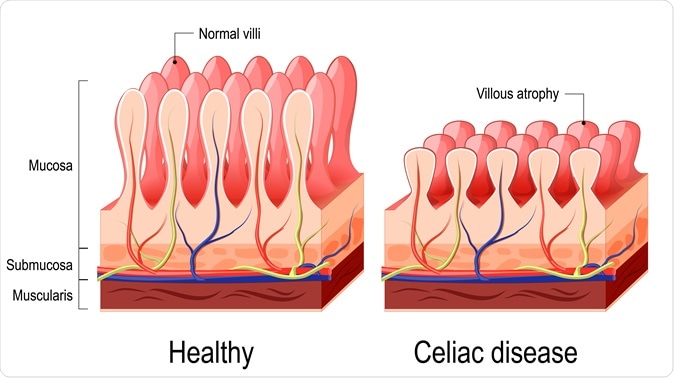

Celiac disease is a genetically driven chronic immune-mediated disorder where abnormal immune responses to gluten peptides lead to small intestinal mucosal damage. Recent population-based studies in the U.S. indicate that the prevalence of celiac disease is around 1% and approximately 0.5% globally. The threshold of daily gluten that will cause mucosal injury in both adults and children is 10 to 50mg per day – or about 1/100th of a slice of bread.

At present, there is no cure for this condition. The only way to keep the intestine healthy is to avoid gluten at all costs, which is sometimes a costly affair, besides the difficulty of ensuring that food sold in the marketplace is always completely free of gluten. Besides these economic and health-related issues, patients find it difficult to eat out, with the uncertainty of finding gluten-free food.

When celiac disease strikes, the only thing doctors can do is to prescribe drugs which suppress the immune system. Though this type of treatment does relieve some aspects of the disease by weakening the immune attack on the gut, there is an associated increased risk of infection. Moreover, many of these drugs have side-effects.

Celiac disease can cause symptoms including abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Long-term complications of celiac disease may include malnutrition, accelerated osteoporosis, nervous system problems and problems related to reproduction. Currently the only available treatment for patients with celiac disease is maintaining a gluten-free diet, which involves strict, lifelong avoidance of exposure to gluten proteins from wheat, barley, and rye, which is not always effective.

Celiac disease. Normal villi and villous atrophy. Image Credit: Designua / Shutterstock

A new approach

In the present approach, the immune system is not suppressed but outwitted using its own tools to turn the course of the disease back by striking at the root – the recognition of the gluten protein as a foreign (“non-self”) antigen.

The researchers concentrated on producing a nanoparticle made up of a biodegradable material, which incorporates a major gluten protein called gliadin. This nanoparticle is meant to function as a Trojan horse, sneaking past immune defenses by concealing the gluten allergen in a host-friendly covering. The hope is that the immune system will ignore the nanoparticle injected into the patient’s circulation since it doesn’t sense any bad or toxic signals. The nanoparticle has been in the making for several decades, in Stephen Miller’s laboratory.

In the next step, the nanoparticle, not being particularly useful to the body, will be engulfed by macrophages, which are the immune cells concerned with removing debris and waste material produced by normal wear and tear, from the body. However, macrophages are also antigen-presenting cells, and the way they present antigens (or allergens) to the soldier cells of the immune system determines the antigen’s fate. If the macrophages introduce the antigen as one which belongs to the body itself (as “self-antigen”, in other words), the immune system accepts it without question. From then on, the researchers hope, the immune recognition of gluten as something foreign and to be attacked will be reset to a more normal setting.

The study

In the phase 2 clinical trial, the gliadin-containing nanoparticle CNP-101 was introduced into patients with celiac disease. One week later, the patients were given gluten for a period of 14 days. A control group of celiac patients exposed to gluten at the same time showed significant immune responses with resulting injury to the small intestine mucosa. However, the CNP-101-treated group had only a tenth of the inflammatory response to gliadin shown by the untreated group. This showed that the nanoparticle injection could prevent gluten-associated inflammatory injury.

Implications

Celiac disease was chosen as the target for the CNP-101 nanoparticle-based therapy because of the known nature of the causative antigen – gluten in diet. In many other autoimmune conditions such as lupus, the exact antigen that triggers the inappropriately directed immune response remains unknown despite intensive research attempts.

Veteran immunologist and researcher Stephen Miller says, “This is the first demonstration the technology works in patients. We have also shown that we can encapsulate myelin into the nanoparticle to induce tolerance to that substance in multiple sclerosis models, or put a protein from pancreatic beta cells to induce tolerance to insulin in type 1 diabetes models."

The CNP-101 nanoparticle was developed by COUR Pharmaceuticals Ltd (a biotechnology company founded by Miller with others), under a license from the researchers, and given Fast Track status by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Takeda Pharmaceuticals has joined hands with COUR to develop this investigational drug commercially and sell it globally. COUR looks forward to taking the approach further to induce immune tolerance in peanut allergy and multiple sclerosis, initially, and then other autoimmune conditions over time, according to John Puisis, the president and CEO of COUR.